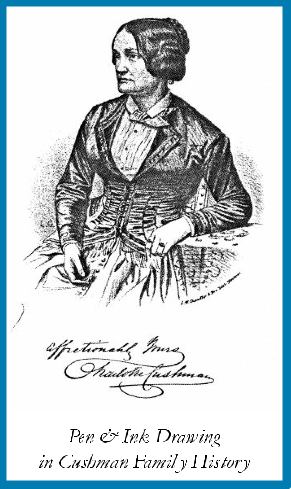

For my first subject I chose Charlotte Saunders Cushman, a world-renowned tragedienne in the mid-1800s. And yes, she is my ancestor—my 5th cousin thrice removed.

I have vivid memories of my father telling my sister and me about the visits his "Aunt Charlotte--the famous actress," made to his home in Plymouth (in Amador County CA) when he was a child. I paid little attention to such things in those days, but about 25 years ago, when I became interested in researching our Cushman family history, I discovered that famous lady in the personage of Charlotte Saunders Cushman.

Though my father had miscalculated his relationship to Charlotte, I'm sure he always thought of her as his auntie, and would be pleased that I learned so much about her, and have passed that information along to other family members, and now to the readers of this blog.

Charlotte was born in Boston on 23 July 1816 to Elkanah Cushman and his second wife, Mary Eliza Babbitt. As a child, Charlotte’s gifts for mimicry and "play-acting" were evident to her brothers and sister and the other children growing up on Richmond Street, but music was the focus of Charlotte’s dreams of becoming a performer.

Though barely in her teens, her rich contralto voice attracted the attention of professional singers and teachers who worked with her until she made her operatic debut as Countess Almaviva in The Marriage of Figaro at the Tremont Theater, Boston, on 8 Apr 1835.

Rave reviews followed, and her success as an opera singer was within her grasp. In the fall of 1836, Charlotte traveled to New York, then sailed to New Orleans where she was booked to appear in the brand new St. Charles Theatre. However, the grueling 9-day voyage, coupled with the change in climate and the vocal strain brought on by trying to conform to roles beyond her range, ruined her singing voice, and the resultant bad notices ended her operatic career before it even began.

She was barely 20 years old, and the sole support of her mother and three siblings. It was imperative that she earn the money that would enable her to meet that responsibility. Although bruised but intact, her Yankee spirit prevailed, and she turned her magnificent speaking voice and her great gift for role-playing to the legitimate theater.

That was the world’s good fortune, and for 40 years, Charlotte Cushman reigned as the world’s best known, most beloved tragedienne. She had one of the most enduring careers the theater has ever known, playing opposite every renowned actor on both continents.

She was not an overnight success, but after many benefits and regional performances, Charlotte made her professional debut playing Lady Macbeth opposite the great William Macready, performing with him in Philadelphia and New York.

An audience member summed up the production when he said that "even with this great and cultivated artist (Macready), she held her own. She had not his experience, but she had genius. There were times when she more than rivalled him; when in truth she made him play second."

Back in Boston at the Melodeon Theater for three weeks in October 1844, Charlotte played opposite Macready in a series of plays she hoped would fully display her superior range: Queen Gertrude, Lady Macbeth, Goneril, and Emilia.

Before the brightest lights of Boston—Charles Sumner, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Joseph Story, Daniel Webster—she did her best to show what a Boston girl could do alongside London’s Macready.

Critically, Boston approved. It found her Emilia "a new revelation." Her withering contempt for Iago, her "grandeur of tone," almost buried Macready’s Othello. The audience recalled her with cheers.

Her London debut was at the Princess’s Theater, starring as Bianca in Milman’s Fazio on 13 Feb 1845. London had known Milman’s play for years. Critics considered it old-fashioned, but Charlotte was determined to give it new luster. What happened that night is theatrical legend, recorded by many critics of the time.

Audience tension that had been building during a crucial scene suddenly welled up and broke loose in a storm of applause. Charlotte was completely overcome with the passion of the scene and could only lie still for a time, unable to respond "to the ringing bravos that burst over her."

When finally she arose, she "beheld an ovation. Hats and handkerchiefs filled the air, roaring cheers rocked the Princess’s from pit to topmost gallery, from aisles to whiskey seats. Applauding men stood on the benches; those in the boxes waved and shouted." In a sudden wave of relief, Charlotte knew that her English career was assured.

The final scene of that play is Bianca’s dying scene. When at last she pressed her heart and sank to the floor in a dying heap, "the scattered house exploded." She rose to cheers and bouquets.

Among many glowing reviews of that performance, the London Sun expressed an opinion that rapidly swept through England: "America has long owed us a heavy dramatic debt for enticing away from us so many of our best actors. She has now more than repaid it by giving us the greatest of actresses, Miss Cushman. Since the memorable first appearance of Edmund Kean in 1814, never has there been such a debut on the boards of an English theatre. She is, without exception, the very first actress that we have."

The rest of her repertoire delighted audiences and critics alike, and she stayed on for an unprecedented 84 nights to play Bianca, Rosalind, Mrs. Haller, Lady Macbeth, Emilia, Beatrice, and Portia. On 4 Mar 1846, when the curtain came down on her performance of Mrs. Haller in The Stranger, the London Times had "hardly ever known such audible weeping in an audience."

Charlotte was the compleat performer. She used her body and voice to achieve many effects. She was also a skilled makeup artist who could look as young and beautiful as any ingenue, or as old and withered as any character role required.

On 10 Jun 1846, when she sprang into the moonlight as the tattered old hag, Meg Merrilies, in Guy Mannering, London saw a towering sibyl with bony arms extended, tense, rigid in fluttering rags, coils of hair escaping the folds of twisted kerchief. She darted a claw at actor Henry Bertram, and when a voice "from another world" began crooning a lullaby, the audience’s blood ran cold.

In the final scene of Guy Mannering, Meg’s dying agonies forced some women in the audience to cover their faces so as not to view the terrible writhing. "Transfixed, awe-struck expressions followed the ragged heap’s final quiverings." When the curtain closed, the audience burst into "screeches of applause; hats peppered the air. A few moments later, when Charlotte bounded through the curtains with her own dark hair brushed free of the wig, her face washed clean of its swarthy wrinkles, a new frenzy shook the house."

Like many dramatic actresses of her day, Charlotte would occasionally take on "trouser roles," i.e., some of the male roles in Shakespearean and other classic plays. On several occasions, she played Romeo to her sister Susan's Juliet. Susan's theatrical life was short-lived, however, as she met and married Sheridan Muspratt soon after arriving in England.

As Charlotte toured England, other journals wrote glowingly of her gifts, summed up by a Liverpool critic who wrote, "Miss Cushman is a very extraordinary woman. She has already attained a degree of celebrity such as no other American ever arrived at, and what is more, such as no other American ever merited. She is likely to become still more distinguished among us, for it is long—very long—since an actress possessing so much talent appeared upon the English stage."

Similar audience response and critical acclaim awaited Charlotte in Edinburgh and Dublin and throughout the provinces, and later throughout all of Europe. She followed that with another tour of the U.S. starting in 1849 and ending with a triumphant performance as Meg Merrilies at the Broadway Theatre on 15 May 1852. She returned to Europe for a well earned vacation, then revived her career and continued performing as an actress, then as a platform reader, touring both continents until her retirement nearly 20 years later.

Charlotte died 18 Feb 1876. She is buried in Mt. Auburn Cemetery, Boston, where a monument has been erected in her memory.

At some point shortly after the turn of the 20th century, stone-ground lithographs of her image, along with artists' renderings of scenes of some of her most popular roles were created on a very handsome cigar box label, and can still be found occasionally in the ephemera collectibles market.

In 1915 Charlotte Cushman was voted into New York’s Hall of Fame for Great Americans, partly at the urging of actresses Jane Cowl, Katherine Cornell, and Minnie Maddern Fiske. However, the actual ceremony did not occur until ten years later—21 May 1925—when busts of John Marshall, William T. Sherman, Asa Grey, and Harriet Beecher Stowe were also unveiled. The Cushman bust, by Francis Grimes, was financed by popular subscription. Otis Skinner delivered the address; John Drew, as president of the Players Club, presented the bust; and Dr. Allerton Seward Cushman unveiled it.

=======================

References to Charlotte Saunders Cushman as a popular American tragedienne may be found in most modern encyclopedias, theater arts textbooks, and numerous histories of the theater, as well as in many collections of the biographies of great American women.

And, of course, she is covered extensively in the "Historical and Biographical Genealogy of the Cushmans: The Descendants of Robert Cushman, the Puritan, From the Year 1617 to 1855" by Henry Wyles Cushman.

I am privileged to own a volume entitled "Charlotte Cushman," written by Clara Erskine Clement and published in 1882 as part of the American Actor Series. It covers Charlotte's professional life and includes some of her writings.

In 1970, Yale University Press published "Bright Particular Star - The Life and Times of Charlotte Cushman" by Joseph Leach. Something less than a best-seller, it remained virtually unread on library shelves throughout the 1970s, and has been out of print for many years.

Some time in the late 1980s or early 1990s, a New York friend and I were vacationing in Connecticut, and drove up to Yale University. While there, I asked a press officer if they had an old copy of the book. They did not, but happily they directed me to an antiquarian book dealer who did.

================

Additional Sources:

- The United States Magazine and Democratic Review, Vol. 16, Apr 1845, "Mr. Forrest’s Second Reception in England" (author not cited).

- Littell’s Living Age, Boston, Vol. 26, 3Q 1850, NEW BOOKS

- The International Monthly Magazine of Literature, Science and Art, Vol. 1, No. 5, 29 Jul 1850, Authors and Books

- The United States Magazine and Democratic Review, Vol. 28, Feb 1851, Notices of New Books

- The United States Magazine and Democratic Review, Vol. 29, Aug 1851, Miscellaneous—Broadway Theatre

- The United States Democratic Review, NY, Vol. 40, No. 6, Dec 1857, "The Drama in America" (no author cited), p. 558

- Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, NY, Vol. 28, Jan 1864, Editor’s Easy Chair, p. 275

- The Atlantic Monthly, Boston, Vol. 21, Apr 1868, ART, "Matheiu’s Busts of the Composers" by J. S. Dwight, p. 503

- The Galaxy, NY, Vol. 13, No. 1, Jan 1872: Nebulae by The Editor, p. 147

- Scribner’s Monthly, An Illustrated Magazine for the People, NY, Vol. ?, Jan 1872, Culture and Progress at Home—CHARLOTTE CUSHMAN, pp. 378 & 379

- The Galaxy, NY, Vol. 21, Issue 4, Apr 1876, Nebulae by The Editor, p. 580

- Scribner’s Monthly, An Illustrated Magazine for the People, Jun 1876, "Charlotte Cushman" by John D. Stockton, pp. 262-266

- The Galaxy, NY, Vol. 24, No. 2, Aug 1877, Nebulae by The Editor, pp. 291-92

- Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Vol. LVII, Aug 1878, Editor’s Literary Record, p. 465 (a review of Emma Stebbins’ book: Charlotte Cushman: Her Letters and Memories of her Life) Houghton, Osgood, and Co.

- The North American Review, Vol. CXXVII, 1878, Contemporary Literature, pp. 163 & 164 (another review of Emma Stebbins’ biography of Charlotte)

- The Atlantic Monthly: A Magazine of Literature, Science, Art, and Politics, Vol. XLII, No. CCL, Aug 1878, RECENT LITERATURE, pp. 251-252 (yet another review of Stebbins’ book)

- The Atlantic Monthly, A Magazine of Literature, Science, Art, and Politics, Vol. XLIX, pub. in Boston, Jun 1882, BOOKS OF THE MONTH, p. 858

- The Century, A Popular Quarterly, pub. in NY, Vol. 35, Issue 3, Jan 1888, "John Gilbert" by Ranken Towse, p. 380

- Harper’s Monthly Magazine, pub. in Pearl Street, Franklin Square NY, Vol. LXXIX, Nov 1889, "A Century of Hamlet" by Laurence Hutton, pp. 866-884, cited ref. on p. 884

- The Atlantic Monthly, pub. in Boston, May 1892, "Severn’s Roman Journals" by William Sharp, pp. 631-645

- New England Magazine, An Illustrated Monthly, pub. in Boston by Warren F. Kellogg, Nov 1893, "The Friendship of Edwin Booth and Julia Ward Howe" by Florence Marion Howe Hall, pp. 315-320 (cited ref. on p. 317)

- The New England Magazine, Vol. 16, No. 1, Mar 1894, "Experiences During Many Years" by Benjamin Penhallow Shillaber, p. 30. (Apparently the author was a journalist on the Gazette for many years. The scene he has recollected had to have taken place around 1873, 74 or 75—when Charlotte was battling breast cancer.)

- The New England Magazine, Vol. 18, No. 1, Mar 1895, "Massachusetts in the Civil War" by Thomas S. Townsend, pp. 3 - 21 (cited ref. on p. 10)

NOTE -- this section added on 1/22/2011 -- A reader left a fascinating comment, which I have added here, followed by more info about the books mentioned.

Deborah Anne wrote:

"It is lovely that you're writing about your distant relative - I have to point out that the picture you identify as "The Cushman Sisters: Charlotte and Susan" is not correct. The other woman is Charlotte's first wife Mattie Hayes with whom she lived and travelled for about 10 years. In fact, if you have not read the books WHEN ROMEO WAS A WOMAN or ACROSS AN UNTRIED SEA you haven't scratched the surface of this fascinating woman. They are the latest scholarship I'm aware of on her and the first is the basis of a new play called CASA CUSHMAN being developed by the writer of THE LARAMIE PROJECT. There's also a solo play called THE LAST READING OF CHARLOTTE CUSHMAN, which I've never seen or read but seems to have received excellent reviews."I am grateful to Deborah Anne for taking the time to share her knowledge, and will hopefully be able to get those books read in the near future.

Here is more info about the books, should my readers wish to explore the matter on their own. If you do, Dear Reader, please come back and share your thoughts here.

- When Romeo Was A Woman by Lisa Merrill -- uses Cushman's and her associates' diaries and letters to explore further the actress's romantic "friendships" with other women -- Amazon link -- http://www.amazon.com/When-Romeo-Was-Woman-Triangulations/dp/0472087495 -- read a more detailed description there, and use the Look Inside feature to read a few pages.

- Across an Untried Sea: Discovering Lives Hidden in the Shadow of Convention and Time by Julia Markus -- discusses the many women in Charlotte's life - Amazon link: http://www.amazon.com/Across-Untried-Sea-Discovering-Convention/dp/B000HWYURU/ref=ntt_at_ep_dpt_6 -- again, you can read a more detailed description and reviews there, and use the Look Inside feature to read a few pages.

These books have also been cited in other theater/gay/history books:

- Between Women: Friendship, Desire, and Marriage in Victorian England by Sharon Marcus

- Cast Out: Queer Lives in Theater (Triangulations: Lesbian/Gay/Queer Theater/Drama/Performance) by Robin Bernstein

- Her Best Shot: Women and Guns in America by Laura Browder

- Wearing the Breeches: Gender on the Antebellum Stage by Elizabeth Reitz Mullenix

- Victorian Shakespeare, Volume 1: Theatre, Drama and Performance by Gail Marshall